What Does Serial Number on Money Mean?

Serial Numbering

Numbering on modern notes

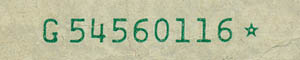

The only type of U.S. currency commonly found in circulation today is the Federal Reserve Note. Up through Series 1995, all FRNs had serial numbers consisting of one letter, eight digits, and one letter, such as A12345678B; now only the $1 and $2 notes still use this form. The first letter of such a serial number identifies the Federal Reserve Bank which issued the note; since there are twelve FRBs, this letter is always between A and L. The last letter has no particular meaning; it merely advances through the alphabet as each block of notes is printed. The letter O is not used because of its similarity to the digit 0, and the letter Z is not used because it is reserved for specimen notes or test printings. On some notes, a star appears in place of the last letter. The star indicates that the note is a replacement for another note that was found to be defective or damaged during printing . The eight digits can be anything from 00000001 to 99999999, but in recent years the highest serial numbers have been reserved for the BEP’s souvenir uncut sheets of currency, and therefore not issued for circulation.

The recently redesigned Federal Reserve Notes, beginning with Series 1996, have two letters rather than one at the beginning of the serial number. On these notes, the first letter corresponds to the series of the note: Series 1996 notes have serial numbers beginning with A; Series 1999, numbers beginning with B; Series 2001, with C; Series 2003, with D; Series 2003A, with F; Series 2006, with H; and Series 2006A, with K. The notes of Series 2004, beginning the next redesign, have serial numbers beginning with E; Series 2004A, with G; Series 2006, with I; Series 2009, with J; Series 2009A, with L; Series 2013, with M; and Series 2017, with N. (Note that the 2006 series designation has been used for notes of two different design generations, and that it is paired with a different serial prefix letter in each case.) The second letter of each serial number now represents the issuing FRB and ranges from A through L. The last letter still can be anything but O or Z, and is still occasionally replaced by a star, with the same meaning as before.

Numbering on obsolete notes

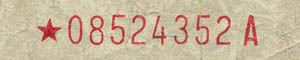

On some older note types which are no longer commonly found in circulation, the letters of the serial number were used differently. United States Notes, Silver Certificates, and Gold Certificates were not issued by the Federal Reserve Banks, so the first letter of their serial numbers, like the last letter, only served to distinguish different blocks; it had no particular meaning. The order of the blocks was therefore different as well: after a complete block of serials with the letters A..A was printed, the next block would use letters B..A, and so on. The letter Z was still in use then, so after Y..A would come Z..A and then A..B. (Note: presumably the Z would also have been used on Federal Reserve Notes back then, if it had been needed, but the serial numbers of the FRNs never got so high.) The letter O has always been skipped, however. For these older note types, replacement notes had a star in place of the first letter of the serial, rather than the last letter.

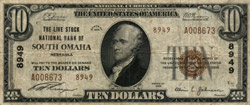

National Currency used a different numbering system entirely–in fact, more accurately, it used two different systems, since a change was made to the numbering in 1933. The first small-size Nationals, printed between 1929 and 1933 and known as “Type 1”, had serial numbers consisting of six digits with a letter at each end, such as A012345A. For each issuing bank, six blocks of serial numbers were used simultaneously: the first six notes would be numbered A000001A through F000001A, the next six A000002A through F000002A, and so on. If a single bank issued more than six million notes of a denomination (an extremely rare occurrence), then F999999A would be followed by A000001B through F000001B and so forth. In addition to the serial number, each note also carried the charter number of the issuing bank, printed in black on each end of the note. The “Type 2” National Bank Notes printed from 1933 to 1935 used a different serial number format, with the last letter omitted; thus the notes had serials such as A012345. In this system, only one block was used at a time for a given bank, so the sequence of serial numbers would be A000001, A000002, A000003, and so on. If the A block was exhausted, the letter would be changed to B; again, this happened quite rarely. These notes also had the issuing bank’s charter number printed four times rather than two; the two added charter numbers were printed in brown, next to the serial numbers. In neither of the two numbering systems were replacement notes indicated by stars; instead, a defective note was replaced by printing a new note with the identical serial number, including the letter(s).

Federal Reserve Bank Notes, despite their similarities to Nationals, followed the same serial numbering system as Federal Reserve Notes, since they were issued by particular FRBs.

Prior to 1928, the large-size notes of all types used a variety of different serial numbering systems. The number of digits in a serial number, the presence of prefix and suffix letters, and the meaning of those letters when they appeared all varied considerably over time and between types. On many early notes, decorative symbols were used instead of letters at the beginning and/or end of a serial number. Some early National Bank Notes even had two different serial numbers with distinct meanings, one counting notes issued to a particular bank and the other counting the total number of notes issued to all banks.

Star notes

Star notes are replacements for other notes damaged during the printing process. The term “star note” comes from the small star which replaces one of the letters in the serial number on these notes. On Federal Reserve Notes and Federal Reserve Bank Notes, the star is placed at the end of the serial number; on notes of other types, it is placed at the beginning.

If a damaged or misprinted note is discovered before the third printing stage, in which the serial numbers are applied, it is simply discarded and destroyed. But if a defective note is found after the serial numbers have been printed, it must be replaced by another note so that the count of notes issued will remain accurate. Until about 1910, the BEP would actually print a replacement note with the same serial number (including letters) as the defective note; however, as production levels increased, this became rather time-consuming.

To speed up the process, star notes were introduced. The BEP first prints a small quantity of notes with star serial numbers, and then uses these to replace any damaged or misprinted notes discovered during the main print run. The serial number on a star note is not related to the serial number of the defective note it replaces; indeed, a defective note may even be replaced by a star note from a different series, or (in the case of Federal Reserve Notes) from a different Federal Reserve district.

Even after the introduction of star notes, however, the BEP continued to use the old method of individually printed replacement notes in some instances. For any notes which were printed in extremely small print runs, it was simpler to reprint each defective note than to prepare a tiny number of star notes in advance. Therefore, no star notes were printed for the small-size National Bank Notes, $5000 or $10000 Federal Reserve Notes, or $10000 or $100000 Gold Certificates. None of these have been in production since the 1940s; and since that time, the BEP has been using the system of star replacement notes for all denominations and types of U.S. currency.

Three different-looking stars have been used in these replacement serial numbers over the years. Most recently, a small hollow star is used; some early small-size notes used a larger solid star; all large-size star replacement notes used a large hollow star. It should be mentioned that a few series of large-size notes can be found with a solid star in the serial number, but these are not replacement notes. Rather, the solid star is one of many different characters that were used to mark one or both ends of a serial number in the years before it became traditional to use only alphabet letters for that purpose.

More technical considerations

Until 1952, nearly all U.S. currency had the serial numbers applied using a system called consecutive numbering, in which the serials ran sequentially down each sheet. (The exception was Nationals, which mostly used sheet numbering, in which all notes on a sheet had the same serial number and had to be distinguished by their plate position letters.) Consecutive numbering was simple and allowed great flexibility in the lengths of daily print runs; each printing could simply pick up where the last had left off. However, the process of cutting the sheets apart so that the notes would end up stacked in correct serial number order was a slow one.

To increase efficiency, the BEP when upgrading from 12-subject to 18-subject sheets adopted a new serialling system known as skip numbering. In this method, notes with sequential serial numbers actually come from different sheets. The numbers are placed so that when a hundred freshly serialled sheets are stacked, the pile can be cut directly into packs of 100 sequentially-numbered notes, already in order and ready to be strapped and packaged. The serial numbers of the notes on a single sheet, therefore, are far from consecutive; the range from the lowest to the highest number on a sheet may be anywhere from several thousand to several million.

The exact details of the skip numbering have varied over the decades, as the number of sheets in a standard print run has been increased several times, and the size of the sheets themselves has increased from 18 notes to 32 and now to 50. However, two basic systems have been used. For all 18-subject sheets (1952-1968), 32-subject sheets with conventional serials (1957-1979), and 32-subject sheets serialled on COPE (1971-present), the skip between serials on each sheet is equal to the number of sheets in the print run. In contrast, for 32-subject sheets serialled on LEPE (2012-present), and all 50-subject sheets (2013-present), the skip between serials on each sheet is always just 100. (So effectively, LEPE prints each run as many small 100-sheet sub-runs.)

The result is that there is a mathematical relationship between each note’s serial number and its plate position; but this relationship is complex and depends upon the sheet size, the overprinting type, and potentially the standard run size in use at the time the note was printed. Still, for those who know the code, checking a note’s plate position against its serial number can serve as a subtle test of the note’s genuineness.

As an example, from about 1990 to the present, the BEP has printed $2 through $20 notes (and until recently, $1 notes as well) in COPE print runs of 200,000 sheets of 32 notes, or 6,400,000 notes total. Each such print run is assigned a range of 6,400,000 consecutive serial numbers. The notes on any given sheet have serial numbers separated by skips of 200,000. For example, the first print run will receive serial numbers 00000001 through 06400000. The first sheet of the run will have numbers 00000001, 00200001, 00400001, and so on through 06200001; the second sheet will have serials 00000002, 00200002, …, 06200002; and the 200,000th and last sheet will be numbered 00200000, 00400000, …, 06400000. (Note: in practice, the sheets within each print run are actually numbered backward, so that the highest numbers will end up at the bottom of the printed stack. Thus the “first” sheet mentioned here is actually the last sheet to be printed, and vice versa.)

The numbers on each sheet are arranged in a somewhat complicated pattern, corresponding to the rather quirky numbering of the 32 positions on the printing plate. For the first sheet of the run above, the plate positions and serial numbers would be laid out like this:

| A1 00000001 | E1 00800001 | A3 03200001 | E3 04000001 |

| B1 00200001 | F1 01000001 | B3 03400001 | F3 04200001 |

| C1 00400001 | G1 01200001 | C3 03600001 | G3 04400001 |

| D1 00600001 | H1 01400001 | D3 03800001 | H3 04600001 |

| A2 01600001 | E2 02400001 | A4 04800001 | E4 05600001 |

| B2 01800001 | F2 02600001 | B4 05000001 | F4 05800001 |

| C2 02000001 | G2 02800001 | C4 05200001 | G4 06000001 |

| D2 02200001 | H2 03000001 | D4 05400001 | H4 06200001 |

The simplest way to summarise this is to note that the sheet is divided into four quadrants, and within each quadrant, the numbering proceeds down the columns. The plate position codes have a number for the quadrant and a letter for the position within that quadrant. These codes are actually printed on the notes; they appear in tiny type on the face of each note, usually toward the upper left (though the placement does vary by denomination).

As a result, serial numbers 00000001 through 00200000 will all come from position A1, numbers 00200001 through 00400000 will all come from position B1, and so on to numbers 06200001 through 06400000 from position H4. Then the cycle of position codes will repeat in the next print run, with serial numbers 06400001 through 12800000, and keep repeating through the entire block of notes. When fifteen press runs are completed, the serial numbers have reached 96000000. The sixteenth run then begins again with serial number 00000001, and the suffix letter of the serial number is advanced by one. Since the number 00000001 always falls at the beginning of a print run, the cycle of serial numbers and plate position codes will be the same in every block.

A similar principle applies to the higher-denomination notes, the $50 and $100, though the details are slightly different. These are printed in smaller runs, of 100,000 sheets. The serial numbers on each sheet follow the same pattern described above, except that the skip between notes on a given sheet is 100,000 instead of 200,000. The first print run thus receives serial numbers 00000001 through 03200000, the second 03200001 through 06400000, and so on. Thirty-one of these runs bring the serial numbers up to 99200000, and then the next run begins at 00000001 of the next block. As a result, serial numbers 00000001 through 00100000 fall in position A1, numbers 00100001 through 00200000 in position B1, and so on.

Maximum serial numbers

As just mentioned, all notes currently printed for circulation have serial numbers no higher than 96000000 (or 99200000, for $50 and $100 notes). However, these maximum serial numbers have varied over time; older notes can sometimes be found with substantially higher serials.

On the large-size notes, before 1928, serial numbers were printed without leading zeroes; thus the first few notes of a series might have had serial numbers A1A, A2A, …, A9A, A10A, and so on. When the serial numbers became inconveniently long, they would begin again at 1 with different prefix and/or suffix letters. Eventually the maximum serial number 100000000 (one hundred million) became fairly standard for most types.

When small-size currency was introduced in 1928, one change that was made was the introduction of leading zeroes in the serial numbers, so that every serial number would be eight digits long. The nine-digit number 100000000 continued to be used on the last note of each block, but had to be hand-stamped on that note, because the numbering equipment only had room for eight digits. Around 1935, therefore, the BEP stopped using this number. Instead, when the automated numbering rolled over from 99999999 to 00000000, the note with serial number zero would simply be pulled as an “error” and replaced by a star note.

Production continued this way, with a maximum serial number of 99999999, until the 1970s. By that time, the BEP was printing notes in sheets of 32, as today, but a standard press run was only 20,000 sheets, or 640,000 notes. The first run would be given serial numbers 00000001 to 00640000, the second 00640001 to 01280000, and so on to the 156th, with numbers 99200001 to 99840000. At this point, another full run would take the serial numbers over 99999999, so the 157th run consisted of a mix of regular notes (numbered 99840001 to 99999999) and star notes (with unrelated serial numbers). The 158th run would then begin at 00000001 of the next block.

This 157th run was inconvenient to produce, since it required an unusual setting of the numbering equipment to print regular and star notes in the same run. Therefore, during the production of Series 1974, the BEP stopped using this one atypical run at the end of each block. The 156th print run still had the normal 20,000 sheets, and was numbered normally, 99200001 to 99840000. But then the next run would start at 00000001 of the next block, and the numbers above 99840000 would not be used at all.

Several years later, the standard print run was increased to 40,000 sheets, or 1,280,000 notes. The 99,840,000 notes of each block were then produced in 78 runs instead of 156, but the maximum serial number was unaffected. However, when the press run was increased to 100,000 sheets, or 3,200,000 notes (during production of Series 1981), a change resulted: Now the first run of each block received numbers 00000001 to 03200000, the second, 03200000 to 06400000, and the 31st run, 96000001 to 99200000. The remaining 800,000 serial numbers were not enough for another run, so after 31 runs, the numbering would restart at 00000001 of the next block. The maximum serial number therefore became 99200000.

Finally, during printing of Series 1988, the standard press run for notes of $20 and below was increased to 200,000 sheets, or 6,400,000 notes. Now each block consists of fifteen such runs, totalling 96,000,000 notes; the maximum serial number for these notes is thus 96000000. But the $50 and $100 notes are still printed in runs of 100,000 sheets, so that serial numbers up to 99200000 are still used.

One additional comment: as mentioned above, the uncut sheets of currency sold by the BEP in recent years have serial numbers above these maxima. (Much smaller press runs are used for these sheets, since relatively few are produced.) Since the BEP sells the sheets to collectors at a price above face value, these notes are rarely cut apart and circulated; but it does happen occasionally. Therefore, it is not impossible to find in circulation notes of recent series with serial numbers as high as 99999999, despite the lower “maximum” serial numbers given here. For more information, see the page on uncut sheets.