Situated on an important trade route between the Greek mainland and Ionian colonies in Turkey, the island of Rhodes slowly became one of the most powerful maritime powers in the ancient Mediterranean. Most of the islands’ inhabitants lived in three cities: Ialysos, Kamiros, and Lindos. All three polities started striking silver and electrum coinage in the sixth century BCE.

Situated on the northern tip of the island, the city of Ialysos employed an independent weight standard and struck coins that depicted a winged boar, an eagle, or the helmeted head of Athena.

Alternatively, early Kamirosian coins prominently displayed a fig leaf on the obverse and an empty incuse punch on the reverse. Occasionally, the reverse punch included a legend shown by this example. These coins were struck to the Aeginetan weight standard based on a 12.4g stater.

The third main Rhodian polity, Lindos, struck staters to the Milesian weight standard of 14.1g. Most of the coins struck by Lindos depicted the head of a lion with open jaws on the obverse and an incuse square on the reverse.

Despite the islands’ accumulated economic and maritime might, it was a politically fragmented entity. Consequently, the city-state of Athens grew to dominate the region. To cement their power, the Athenians forced the island to join the Delian League in 478 BCE. Athenian hegemony was not destined to last, and towards the end of the Peloponnesian War in 411, the island was freed from their control. Recognizing their own vulnerability, Ialysos, Kamiros, and Lindos decided to formalize the process of joining together under one capital city that they had been undergoing for a while.

According to the ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, the physical process of urban relocation was a singular decision by the islands’ political elite. While the new city of Rhodes, founded in 408 BCE, represented a definitive drive towards unification and a break from the islands’ past fragmentation, the constituent cities did not cease to function as autonomous entities. Kamerios and Lindos certainly continued to exist as independent cities.

The new city of Rhodes immediately began striking a run of coins that would become one of the most recognizable and longest-lasting series in all of the ancient world. Due to their newly formed unity, the Rhodians were capable of retaining their identity and independent coinage despite being subsumed into the massive empire of Alexander the Great. Rhodes was even able to repel a massive siege in 305-303 BCE by Demetrios Poliorketes “the Besieger”, later to become the Antigonid ruler Demetrios I. In fact, it wasn’t until Rome gained control of the region in the first century BCE that Rhodes ceased the independent striking of their silver coinage.

This series of coins was struck according to the “Chian” standard, with a tetradrachm weighing 15.3g. Originating in the sixth century from Chios, a Greek island roughly one hundred miles north of Rhodes, the standard quickly became known as the “Rhodian standard” due to the predominance of Rhodian trade and coinage.

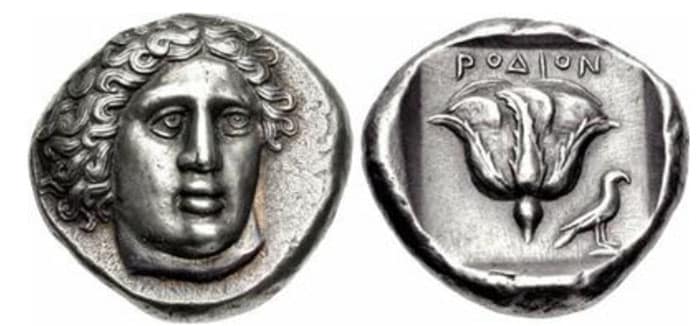

On the obverse, this new coinage depicted the sun god Helios in a forward-facing three-fourths profile. This was a completely new image for the coinage despite the god’s importance to the island. In his history of Rhodes, Siculus describes how Helios saved the island from a disastrous flood and subsequently named it after the nymph Rhodos. As demonstrated by archeological evidence of their religious practices, the local population viewed Helios as their chief god. Helios was even made the patron god of Rhodes.

Due to the unusual style of bust and the facial similarities, it is highly probable that this obverse design was influenced by the contemporary Syracusan coin engraved by Kimon that depicted the nymph Arethusa.

Following a trend common to Greek city-states, the authorities in Rhodes decided to employ a canting, or rhyming, device on the reverse of their coins. The dog rose, or rhodon, is a wild climbing flower that is indigenous to the area and grows abundantly on the island. As a result, the flower not only came to visually represent the city but also phonetically in a form of wordplay. The two, flower and city, almost became synonymous with the flower representing the city’s political authority and the population’s identity as Rhodians.

Unlike the bust of Helios, the rose was not a new addition to the islands’ coinage. The cities of Ialysos and Kamiros had already employed the image on their coins, however, it was not a commonly used design, and examples with it are very rare. For example, during the period of Athenian control after 478 BCE, Ialysos issued a small series of fractional coins with the forepart of a Pegasus on the obverse and a rose on the reverse.

During the period of Macedonian control, the rose continued to be used as a symbol of the city as evidenced by this tetradrachm of Alexander the Great struck between 336 and 323 BCE. The rose mintmark can be seen on the bottom left field on the reverse.

Virtually all official coins in the early period of Rhodes followed this convention of a three-fourths facing obverse head and a reverse rose. Unofficially, Perseus, King of Macedonia, struck a series of pseudo-Rhodian drachmai with a full forward-facing head of Helios. It is believed that these coins were used to pay the king’s Cretian and Rhodian mercenaries.

While the drachm of King Perseus is a pseudo-Rhodian issuance, the moneyers in Rhodes did break from tradition between 304 and 265 BCE when they struck a series of didrachmai with the bust of Helios in full profile facing to the right. The other new feature on the obverse was Helios’s radiate crown. While both the radiate crown and the right-facing bust would be used repeatedly after 304 BCE, this series reflected the first major change in the design of the city’s coinage.

Richard Ashton, the noted numismatist and historian of Rhodian coinage, argued in his 1988 paper Rhodian Coinage and the Colossus that this series was used to promote and raise the money necessary to construct the famous Colossus of Rhodes. Minted from 304 BCE until 265 BCE, this was a limited series, with only a few obverse varieties. Since this design emphasizes the radiate crown, it may have been intended as an accurate representation of the actual colossus and not merely a stylized depiction of Helios.

While on subsequent coins the Rhodian moneyers would switch between the three fourths and full profile busts of Helios, the God’s portrait would almost always have the new radiate crown. High-grade early examples of a Rhodian tetradrachm can cost thousands of dollars, it is quite easy for an astute collector to acquire a quality drachm or didrachm for several hundred dollars.