All coins struck in the United States are struck by a pair of dies. A die is a steel rod with a face that is the same size as the coins that it will be striking. This steel rod will contain the design for one side of the coin. Two of these steel rods (dies) are needed to strike coins. One will have the obverse (front of the coin) design, and the other will have the reverse (back of the coin) design.

The dies are set up in a machine called a coining press so that a planchet (blank) will come between them. In the older coining presses one die would be positioned above the other. The upper die (hammer die) would come down with great force and strike the planchet while it was resting on the lower die (anvil die). The force of the hammer die striking the planchet on the anvil die would place the images from the dies onto the planchet and the result would be a coin as we know it. In the newer coining presses the action of the hammer die is now side-to-side rather than up and down, but the process is still essentially the same, as is the result.

The reality is that the die varieties we enjoy collecting, which includes doubled dies, repunched mint marks (RPMs), over mint marks (OMMs), repunched dates (RPDs), overdates, (OVDs), and misplaced dates (MPDs), are the result of mishaps that occur in the process of making the dies that strike the coins. A working knowledge of the die making process will help us to see how the various die varieties resulted over the years. The technology for making U.S. coinage dies has evolved significantly over the years. Because of these technological advances, most of the die varieties that we enjoy collecting will never be produced again. The only die variety that the Mint has had difficulty eliminating is the doubled die, and we will have more on that later.

In the earliest days at the U.S. Mint, from approximately 1792 through 1836, a Master Die for a given year and denomination was produced by a Mint engraver who carved the central design for a coin directly into the face of the master die. The design elements around the edge of the coin such as the mottos, stars, and date were not carved into the master die. The carved design was cut out of the face of the master die so it was recessed (incuse) on the face of the die.

This master die is not used to strike coins. Because of the number of coins for a given denomination that need to be struck in any given year, it was not feasible to use these hand engraved dies to actually strike coins. Using modern coinage as an example, in 1996 the Philadelphia Mint produced about 6.6 billion Lincoln cents. The average life of a Lincoln cent die is about 1 million coins. Some simple math will tell us that in 1996 the Philadelphia Mint alone would have needed about 6,600 Lincoln cent dies to strike the Lincoln cents produced that year. Of course in the earlier days of the Mint that we are examining here, the yearly mintages were much less than modern mintages. However, the life of a die was also much less than that of modern dies, so it was still very impractical to hand engrave the dies that would strike the coins.

Rather than being struck by the master die, coins are struck by Working Dies. The master die is used as a tool from which the working dies would ultimately be produced. When the engraver was finished carving the central design into the master die, the master die was taken to a machine known as a hubbing press. In the hubbing press the master die was placed above a blank steel rod. With great pressure the face of the master die was lowered and squeezed into the steel rod leaving the impression of the image on the master die on the face of the steel rod. The blank steel rod has a cone-shaped face to allow for easier metal flow into the recessed areas of the die when the pressure from the hubbing press is applied. The new steel rod is known as a Working Hub and it now has the design images in relief (raised) just like on the struck coins. The face of the working hub looks exactly like one side of a struck coin.

These blank steel rods with cone-shaped faces (tops) are used by the Mint in a hubbing press to create master dies, working hubs, and working dies.

This photo illustrates a working hub that was created for the Lincoln cent reverse. If you look carefully, you can see that the images on the face of the working hub are raised and look just like they will appear on the struck coins. The arrows point to grooves along the edge of the hub. They allow for proper alignment of the working hub and the working die when more than one hubbing is needed to complete a satisfactory image on the hub or die being made. The corresponding dies will have raised areas (lugs) in the same locations that fit into the grooves to insure proper alignment.

Because of the hardness of the die steel and the amount of pressure that needed to be applied for the image transfer, it took more than one squeeze (hubbing) of the master die into the face of the working hub to leave a satisfactory impression of the design on the working hub. After it received the first impression, the working hub was removed from the hubbing press and treated with heat (annealed) to relax the molecular structure of the alloy and allow another impression to be made by again squeezing the master die into the working hub. This process of making an impression (hubbing) and heat treating (annealing) was repeated until it was deemed that the image on the working hub was satisfactory.

This is the annealing oven at the Philadelphia Mint (1998). Hubs and dies that needed to be annealed before receiving another impression in the hubbing press were taken to this annealing oven for the heat treatment.

Working hubs produced from the master die were then in turn used in the hubbing press to make the Working Dies. It is the working dies that are then used to strike the coins. Like the working hub, it took more than one squeeze of the working hub into the working die to leave a satisfactory impression of the design on the working die. This meant that the working die had to be removed from the hubbing press after each hubbing and heat treated before receiving the next impression.

This is a working die (left) for the reverse of the Lincoln cent as it appears after being hubbed. Notice that the design is reversed from what you will see on the struck coins. Though difficult to see in the photo, the design is depressed (incuse) in the working die. Arrows point to the raised areas (lugs) around the rim that align to the grooves of the working hub. To the right of the working die we can see some more blank steel rods that can be used to make master dies, working hubs, or working dies.

The primary reason that the master die contained only the central design elements was the fact that the hubbing press that was used to make the working hubs and the working dies was a “screw press”. With this type of press it wasn’t possible to apply enough pressure in the hubbing process to transfer the design elements nearest to the rim onto the hubs and dies. There were also concerns that if any errors were made while punching the design elements near the rim into the master die, much time would be lost when a new master die would have to be started. The design elements around the rim such as the mottos, stars, and date were hand punched or engraved into the working dies.

If it was necessary to have a mint mark on the coins to identify the Mint at which the coins were being produced, the mint mark was the final part of the design added to the working die. A die maker at the Mint used a thin steel rod (punch) that had the appropriate mint mark letter engraved at the one end. Holding the mint mark punch in the appropriate position on the working die he tapped the mint mark punch with a mallet to leave an impression of the mint mark on the working die. It frequently required more than one tap with the mallet to leave a satisfactory impression of the mint mark on the die, and the die maker would repeat the taps with the mallet until the mint mark impression was deemed satisfactory.

In 1836 the Mint introduced the use of the French Portrait Lathe. This was the point at which the Mint started to use galvanos. The galvano is a large model of the design that will appear on the coins. Each galvano is anywhere from twelve to fifteen inches in diameter. This size made it easier for the Mint engravers to work with the design. Just like when the design was engraved directly onto the master die, only the central elements of the design appeared on the galvano. The process of making galvanos evolved significantly over the years.

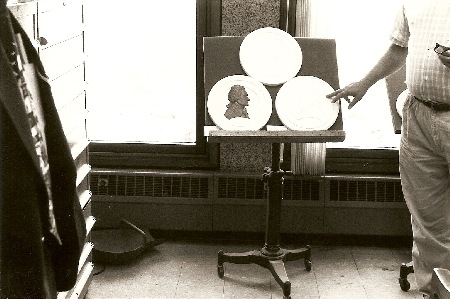

Galvanos for some Mint medals are seen on this display stand during a 1998 Coin World sponsored tour of the Philadelphia Mint.

This is a galvano for the Statehood quarters. It is fixed in position in one of the Philadelphia Mint’s reduction lathes in use in 1998.

This is a galvano for the Statehood quarters. It is fixed in position in one of the Philadelphia Mint’s reduction lathes in use in 1998.

The French Portrait Lathe was a reduction tool that traced out the design on the galvano and engraved that design onto the face of a Master Hub. This process was a slow and tedious one taking anywhere from a day and a half to two days to complete the transfer of the design to the master hub. When finished, the master hub had the design in relief and the face of the master hub was the exact size of the coins that would ultimately be produced with that design.

The master hub could be used over a period of several years since it did not contain the date. Each year it would be used to make a master die for that year. That master die would then in turn be used to make working hubs and the working hubs would be used to make the working dies as in the process described earlier. The remaining design elements would be punched or engraved into the individual working dies.

With the introduction of the Flying Eagle and Indian Head cents the Mint began placing the letters around the rim of the obverse onto the master die. To avoid the mistakes and inconsistencies that could occur if those letters were punched individually, a single circular punch contained the entire arrangement of letters so that they could all be impressed into the master die at one time. At this point the date still did not appear on the master die and was punched into the individual working dies. This was done so that the master die could be used for

more than one year.

In 1867 a different reduction lathe was obtained. It was known as the Hill Reducing Lathe and performed the same operation of transferring the design from the galvano to the master hub. Around 1886 the Mint began placing the letters around the rim of the Indian cent onto the galvano. In 1893 the Mint switched from the screw press (hubbing press) to hydraulic hubbing presses eliminating the problems that they experienced in transferring the design elements near the rim during the hubbing process. Throughout this entire time the date continued to be punched into the individual working dies.

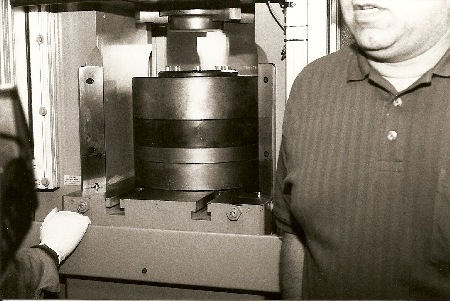

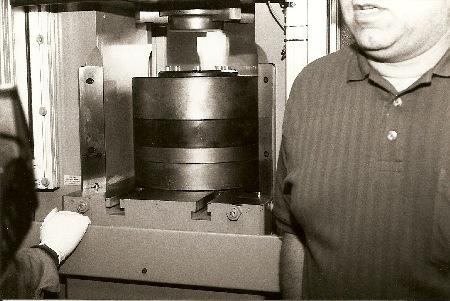

This is a hydraulic hubbing press used at the Philadelphia Mint prior to the introduction of the single-squeeze hubbing process. If a working die was being produced, a working hub was fixed to the central mechanism at the top of the hubbing chamber and a blank steel rod was placed directly below it. When activated, the top of the press lowered the working hub into the steel rod. After receiving the initial impression the incomplete working die was annealed and returned to the hubbing press for another impression. This process was repeated until it was deemed that the working die had a satisfactory image.

In 1907 the Mint introduced the Janvier Reduction Lathe that would remain in use for the remainder of the 20th century. Like the French Portrait Lathe and the Hill Reducing Lathe, it is a pantograph with two arms. As one arm traces out the design on the galvano, the other arm carves the design into the face of the steel rod that would become the master hub.

When the Janvier Reduction Lathe was introduced in 1907, the first two digits of the date began to appear on the galvano and thus on the master hubs. This was done so that the master hub could be used to make master dies over a period of several years. Starting with the Lincoln cents in 1909, the last two digits of the date were engraved into the master die for each year.

By the middle of the 1980’s the Mint started placing the last two digits of the date on the master design (galvano). New master hubs were prepared each year for each denomination. At this time the Mint also started placing the mint mark on the master design for all Commemorative and proof coins.

According to the 1986 Report of the Director of the Mint, the Mint was in the process of developing single-squeeze hubbing presses for the production of working hubs and working dies. According to that document, “During FY86 (Fiscal Year 1986 which actually began in 1985), the Mint further developed a new process for a key aspect of die manufacturing, the hubbing of dies in a single squeeze. When implemented, this will eliminate intermediate annealing and cleaning and the second hubbing operation. It will also avoid the possibility of hub-doubling (doubled die) errors caused by misalignment of the second squeeze. The new process has been used for master dies and work hubs and is in pilot testing for production dies.”

In 1990 and 1991 the Mint began applying the mint mark to the master die for circulation strike coins. After 1994 the mint mark was placed on the master design.

A major turning point for hub and die production in the U.S. Mints came in the summer of 1996 when the Denver Mint opened its own die making shop. Prior to this, all aspects of the die making process were done exclusively at the Philadelphia Mint. The new Denver die shop was equipped with the single-squeeze hubbing presses that the Mint started developing in the mid-1980’s.

This is the hubbing chamber of a single-squeeze hubbing press in use at the Philadelphia Mint in 1998.

The die shop at the Denver Mint does not produce master hubs or master dies. All master hubs and master dies are still produced at the Philadelphia Mint. Master dies for coinage production at the Denver Mint are shipped to the Denver die shop from the Philadelphia Mint’s die shop. The Denver die shop then produces the necessary working hubs and working dies in their die shop. The Denver die shop also produces the unfinished working dies that will be used at the San Francisco Mint. Once received from Denver, the working dies receive their special finishes for proof coin production at the San Francisco Mint.

In Denver the single-squeeze hubbing process was used for the production of cent, nickel, and dime dies during 1996. At that time the Mint was still having difficulty producing quarter dies and half dollars dies with a single hubbing.

By the end of 1996 the new single-squeeze hubbing presses were also installed in the Philadelphia Mint’s die shop so that in 1997 they too began producing dies with the single-squeeze hubbing process. In 1997 some of the problems with the single-squeeze hubbing presses were eliminated and the quarter dies began to be produced by the single-squeeze hubbing method.

Both facilities, Denver and Philadelphia, continued to have problems producing half dollar dies with the single-squeeze hubbing method. Those problems were soon eliminated as well. The Mint subsequently announced that beginning in 1999 all U.S. coinage dies were being produced using the new single-squeeze hubbing process.

In 2008 the Mint announced major advances for the development of the master design models that are used to produce the master hubs. According to the Mint, engravers at the Mint now have the option to continue to make physical models (galvanos) of the coin designs, or they can use sophisticated computer programs to make 3-D computer models of a coin’s design. If the engraver does choose to create the traditional physical models, the completed models can be scanned into the computer using special 3-D scanning equipment. Consequently, whether produced from scratch on the computer or created as a physical model, the coin design ultimately ends up as a 3-D computer image.

Once the coin design is in the computer and deemed satisfactory, new CNC (computer numerical control) milling machines carve the design directly onto the face of a master hub. The Janvier Reduction Lathes in use at the Philadelphia Mint since 1907 are now a thing of the past. The new CNC milling machines can create a master hub in about half the time it took the Janvier Reduction Lathes to do the same job.

Once the master hub is created, it is used to make some test dies that strike sample coins. If there are any problems, the design can be tweaked in the computer and a new master hub created. Once the Mint is satisfied that all is as it should be, the master hub is used to make the appropriate master dies. The remainder of the process remains the same with the master dies being used to create the working hubs, and the working hubs then being used to make the working dies that will be used to strike the coins.

Source: WDV

Intrrsting!